Taylors Falls & St. Croix Falls

A sense of place

HYDROELECTRIC DAM PHOTO © TAYLORS FALLS HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Scenes from the St. Croix

A Historical Overview of the St. Croix River Valley: Taylors Falls & St. Croix Falls Area

Although the sister towns of Taylors Falls and St. Croix Falls are in different states, they share a common history and a scenic, natural beauty that spans from either side of the river that divides them. Picturesque villages with historic main streets dot the St. Croix River banks atop towering bluffs, only slightly breaking the lush forests and wild vegetation around them. To paddle the river or hike a nearby trail evokes a feeling of timelessness, as through traversing a path that has existed just so since the dawn of time. But nature and humans have lent a hand to continually evolve this landscape and shape it into what it is today.

Geology sets the stage

Throughout history, the landscape of the St. Croix River valley has looked radically different. Around 1.1 billion years ago, the earth split along a rift that stretched from Lake Superior all the way down to Kansas, spewing forth lava that would eventually weather into dark, basalt rock. Fast forward to around 550 million years ago when shallow seas dominated the area, depositing sand and sediment which compacted into layers of sandstone on top of the basalt bedrock. Approximately 2.5 million years ago two separate glacial lobes converged, advancing and receding, and sculpting rock terraces in the process. When the last of the glaciers retreated 10,000 years ago, their meltwaters rushed through the valley forming the St. Croix River.

Early human inhabitants

Evidence suggests that humans have occupied the land surrounding the St. Croix River as early as 10,000 years ago. Artifacts such as spearheads, javelin points, tools, and animal kill sites have been unearthed in the region indicating that prehistoric human populations from the Paleo, Archaic, and Woodland cultures either passed through or inhabited the area. It is theorized that the nomadic and skilled Paleoindian hunters of the Ice Age may have contributed to the extinction of giant mastodons and woolly mammoths in North America.

The St. Croix River was used as a trade route between tribes for at least 9,000 years prior to the arrival of Europeans. Unearthed copper from the Lake Superior basin and red pipestone from northern Wisconsin were found in caves and campsites along the river. They likely also traded food and medicine plants, thus introducing new plant species to the area.

The Woodland tradition began around 2,500 years ago and continued until the arrival of Europeans. This culture largely centered around a semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle, following game and seasonal food plants. Circa 1,200 years ago, they developed a technique that would allow them to preserve and store wild rice which led to a population boom in the region with larger permanent base camps. Bison and elk were also once in abundance and it is thought that intensive hunting forced these animals to migrate to other areas.

The Dakota and Ojibwe

The first historical inhabitants of the St. Croix River Valley were the Dakota, largely considered to be part of the late Woodland cultural tradition. Their vast territory between the St. Croix and Mississippi rivers was rich in game, fish, and food plants that were spread across the area, causing a semi-nomadic lifestyle structured around seasonal food resources. The springtime was for processing maple sugar; summer brought the gathering of berries, nuts, roots, and wild greens, and later tending small gardens of corn, beans, and squash; late summer and early fall were spent near the banks of rivers and lakes for wild ricing; in the winter, they moved toward the woods for game hunting. Fishing outposts circled the basecamps in all seasons.

The original homeland of the Ojibwe was near the Atlantic Ocean. Early European settlement and encroachment of other Native American tribes pushed the Ojibwe west into the Great Lakes region, where they established a similar semi-nomadic culture centered around procuring sustenance. While this land had plenty of fish and small game, it lacked the great herds of elk and buffalo that once roamed the Dakota territory and the Ojibwe slowly migrated southward chasing the big game.

For centuries, the two tribes co-existed peacefully. The Dakota allowed smaller bands of Ojibwe access to their hunting lands and frequent contact led to trading, intermarrying, participating in ceremonies together, and creating a common language. However, as greater numbers of Ojibwe migrated toward the river valley, tensions arose over territory and food supply. Around the same time, French voyageurs and fur traders entered the area in search of beaver pelts and other furs, further exacerbating the contentious relationship between the Dakota and Ojibwe.

Ongoing conflict plagued the two great nations throughout much of the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth century, resulting in the Ojibwe gradually increasing their territory in the St Croix River valley. Eventually, the Dakota moved south and west to the plains of Minnesota and South Dakota, leaving the Ojibwe in control of the area until a series of treaties from 1825-1862 opened the land to European settlers, effectively converting millions of acres of tribal lands into private ownership.

Fur Traders Seek their Fortunes

In the late 1600s, French voyageurs began to explore the St. Croix River valley. Coming from the east in canoes, the voyageurs’ route flowed through the Great Lakes to the Bois Brule River to Lake Superior, where they portaged down to the headwaters of the St. Croix carrying enormous loads of supplies, befriending Ojibwe, and claiming territory along the way for New France.

As the European demand for expensive furs grew, French fur traders followed the explorers into the region in search of beaver, mink, otter, and muskrat. Tracing the same route through Ojibwe lands, the fur traders quickly enlisted the help of the native tribe, offering manufactured metal goods such as cooking pots, guns, ammunition, knives, and axes as well as tobacco and alcohol in exchange for the prized pelts. The Ojibwe in turn traded these goods with the neighboring Dakota in exchange for hunting and trapping rights on Dakota land.

In 1727, the French began to trade directly with the Dakota, pitting the tribes against each other in competition for trade goods and hunting territories. By 1736, the Ojibwe and Dakota were interlocked in full-scale war. The French both aggravated land dispute conflicts and attempted to arrange truces, all for the sake of the fur trade: warfare between the Native American tribes made it dangerous to enter either territory and stunted the tribes’ availability to trap fur-bearing animals for the French.

The expansion of New France led to border tensions with the English colonies in the east and the French and Indian War ensued, which ultimately ceded control of the St. Croix River valley to the British in 1763. British fur companies established themselves in Montreal, Canada and soon made their own forays from the north into the valley, but ceaseless Dakota-Ojibwe battles kept fur trapping to a minimum. After the War of 1812, the valley fell under American control, the beaver population became depleted, and European demand for fur waned soon after. The 1837 treaty, which ceded all Dakota and Ojibwe territories between the Mississippi and the St. Croix to the American government, gave way to European settlement and the rise of the logging industry.

Lumbermen Lured by White Pine Forests

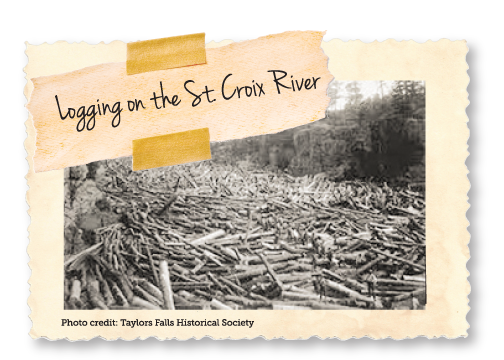

As the fur trade entered its desperate final throes, bold entrepreneurs plotted to seek their fortunes in the fir trade. The St. Croix valley was rich in white pine situated conveniently on the banks of a river that could efficiently transport them to mill and market. The earliest loggers set up camp illegally on Ojibwe land. After the treaty of 1837, the land became government-owned and small crews operating with less than 20 men felled trees with axes during the cold winters, dragged them to the shoreline with oxen or manpower, and used the higher water level after the springtime snow melt to drive their harvest downstream.

The steady growth of the valley’s logging business during the 1840s and 1850s led to larger crews, larger output and larger expenses. The early crews took advantage of unsurveyed, public lands to make their fortunes from free timber, but as land became available for private sale in the mid-1850s, men with capital flocked to the area to purchase large plots. Sawmills continued to spring up along the river banks. By the 1860s, the St. Croix floated more than 200 million board feet on its waters, compared to just 8 million feet from less than 15 years earlier. The influx of logs on the river during this period of growth made it difficult to distinguish ownership of the logs, thus in 1851 the St. Croix Boom Company was formed. Companies branded their cut with their mark and boom owners charged a fee to sort and store them until they could be milled.

A rising demand for lumber in the years after 1865 sprawled lumbermen to every tributary of the St. Croix and even to the tributaries of the tributaries. Pioneers were settling in the Great Plains, relying on St. Croix timber for their homesteads; railroads were beginning to weave through the valley, able to transport lumber to a national market; and the increasingly industrialized nation created both demand and means for greater lumber production. In the mid-1870s the axe was replaced by the crosscut saw that enabled lumbermen to fell pines more swiftly and with less waste. Reliance on waterpower mill sites had ended and steam mills began to pop up along the riverbanks and beyond, further expanding the reach of logging operations.

More logs were being floated down the St. Croix faster than ever before. And along with this increase in logs came an increase in log jams, particularly at Angle Rock near Taylors Falls and St. Croix Falls. Lumbermen had always sought to bend nature to their will, straightening streams and erecting crude dams to control the flow of water, but in the late logging era, the few corporations that dominated the trade made the biggest strides. Large log jams wreaked havoc on the industry. Many men, from mill operators to homestead builders, stood idle awaiting their boon of logs, while companies and their creditors anxiously awaited the timber sale revenue. The greatest jam at Angle Rock in 1886 bottlenecked over 150 million feet of logs for more than three-and-a-quarter miles upstream and took six weeks to dispel. Eager to prevent future jams, lumbermen undertook the building of new dams, including the monstrous Nevers Dam eleven miles upstream from Angle Rock. By 1889, there were 60-70 large, permanent dams throughout the St. Croix watershed.

The 1890s contained the heyday and also the steady decline of the logging era. Loggers had turned 100 miles of drivable river into 840 miles by 1900, churning out 450 million board feet of timber during its peak year in 1890. As the great stands of majestic white pine began to disappear, many lumbermen retired or went off in search of other ventures. The last major drive on the St. Croix River occurred in 1912. The loggers who remained turned their attention to hemlock and other hardwoods, but as these woods lacked buoyancy, they were transported to mill and market by train. Hemlock production peaked in 1920, but these forests too became depleted and by 1930, the large-scale logging operations ceased to exist entirely. By the end of the era, more logs had been driven down the St. Croix than any other river in America. Not since the descent of the glaciers had the St. Croix Valley undergone such a sudden and dramatic change to its landscape and ecology.

Farm Culture Grows

Farming grew up alongside logging. In the 1840s, all the land of the St. Croix valley was part of St. Croix County in the Wisconsin Territory. The first farmers to grab pieces of land provided food to logging camps or worked small sustenance farms. In 1848, Wisconsin became an official state of the union and the year after, the Minnesota Territory was formed. There was much dispute over Wisconsin’s eastern border, with many wishing to keep the St. Croix valley within one state, but eventually a boundary at the river was established, dividing the valley in two.

In the early 1850s, both sides of the border undertook initiatives to recruit settlers to the area. Newspapers lauded the valley’s charm, claiming rich, fertile soils, free from agricultural pests, and the health benefits of the climate. Emigration offices were opened in New York, distributing pamphlets at harbors and overseas in Europe. In addition to the agricultural and climatic advantages, emigration offices were quick to point out the pre-emption act which would allow farmers to claim up to 160 acres of land without having to purchase it first. They could profit from their crops, enabling them to make the money needed to buy the land at a cheaper price before it went up for sale.

These tactics proved successful, luring scores of primarily Scandinavian, German, and Irish immigrants. The population in the valley had swelled so much by 1853 that Wisconsin was compelled to divide St. Croix County into three (Polk County to the north with St. Croix Falls as its seat and Pierce County to the south), while Minnesota formed Chisago County with Taylors Falls as its seat. As the northernmost stop navigable by steamboat, immigrants poured into St. Croix Falls and Taylors Falls at such a rate that in 1856, a bridge was built between the two cities to assist them on their way – the first bridge over the St. Croix River.

Farmers quickly saw the usefulness of the valley’s waterways as a means of transporting crops to a national market, as well as the value of wheat as their main cash crop. While some farmers took advantage of natural crops such as cranberries, blueberries, and wild rice, wheat cultivation was ideal for a pioneer farmer. Wheat did not require large start-up costs, much soil preparation, or in-season maintenance, leaving farmers free to improve their homestead or clear more acreage. It was easily stored and commanded a high market price. By 1863, wheat was in great demand and farmers could use a mechanical reaper and threshing machine to increase their yield while decreasing their labor. Steamboats bursting with St. Croix valley wheat plied their cargo downriver and across the nation.

As the logging industry grew with alarming speed, steamboats were frequently halted by the constant onslaught of floating logs, lumber flotillas, and log jams, hampering the farmers’ ability to ship their produce. It became imperative to turn to a new mode of transportation. The first railroads opened in the early 1870s and continued to advance through the area for two decades. Around the same time, excessive wheat cultivation was taking its toll on the land, exhausting the soil. In 1885, a series of lectures from the University of Wisconsin began in the St. Croix valley to promote dairy farming and crop rotation to achieve better soil conditions. These “institutes,” as the lectures were called, encouraged scientific farming and sharing best practice information and led to the development of county fairs. Some former wheat farmers turned to rye and potatoes, particularly in Minnesota, but by the early 1890s, much of the St. Croix valley had turned to dairying, and creameries and cheese factories began to dot the countryside.

Railroads were of great service bringing the finished product to market, but dairy farmers faced challenges getting the raw product to the factories. In 1893, farmers and businessmen alike pushed for more and better roads and as a result, townships were granted the right to build their own roads. By the turn of the century, dairy products had replaced lumber as the valley’s chief export. Where there had once been a mixture of immigrants from a dozen different countries, there was now the American farmer. Immigrants continued to migrate to the valley, but now they were entering a prospering, self-sustaining community capable of contributing to the country.

A Tale of Two Cities

Although ancient peoples had traipsed through the region for centuries, the first permanent settlers of Taylors Falls and St. Croix Falls came as loggers from the eastern part of the country. The waterpower provided by the mighty falls just upriver from the two towns were a huge draw and important to establishing the beginnings of the industry and the history of the communities.

In 1838, Jesse Taylor became the first man to make a claim near the falls and together with B.F. Baker constructed a sawmill which was never operated on its original site. Upon the death of Baker in 1848, Jesse Taylor sold the mill to Joshua L. Taylor and moved on to Stillwater. Joshua Taylor subsequently moved the mill to Osceola and in 1949, he and his brother, Nathan C. D. Taylor, along with William H. C. Folsom, preempted the site and began laying the foundation for a community. Taylors Falls was platted in 1851 and by 1853, they had established a post office, a mercantile business, built a gristmill, and became county seat for the newly formed Chisago County.

Taylors Falls served as an important supply site for lumbermen due to its location at the head of steam navigation on the river and on the overland Point Douglas-Superior Military Road. Deliveries by steamboat and wagon were stored in a large warehouse in Taylors Falls during late fall and retrieved by sled to provision the logging camps in the winter.

Lumbering prospects also lured Franklin Steele and William S. Hungerford to the falls in 1837-1838. Their group of partners and workmen formed the St. Croix Falls Lumber Company and immediately filed land claims, built several cabins, scouted timberland, and began construction on a sawmill. The mill was not completed until 1842 and with loggers upriver already in the practice of floating their harvest further downstream and steam powered mills on the horizon, Steele sold his share to Caleb Cushing in 1846.

Hungerford and Cushing now controlled most of the land in St. Croix Falls in addition to the mill, but Cushing’s business interests, including politics, mining and land speculation, kept him away from the falls and left his holdings in the hands of inexperienced or unscrupulous agents. The mill was failing and by 1848, the relationship between Hungerford and Cushing had grown so contentious that a legal battle over the land ensued, dragging on for nearly a decade and hindering the growth of St. Croix Falls.

The first wave of immigrants in the 1850s, lured by the Preemption Act, quickly settled Taylors Falls, while Cushing had secured a vast majority of St. Croix Falls via court verdict in 1857. Mismanagement of the Cushing Land Agency further hampered immigration in St. Croix Falls, but by the second immigration wave in the late 1860s/early 1870s, the Cushing Lands were being sold off, and a community emerged. Despite the lands in somewhat of a holding pattern, St. Croix Falls served as county seat for Polk County in 1853.

The Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, German and others came to this area, but because of Vilhelm Moberg’s writings, Chisago County is noted in Minnesota and remembered/celebrated in Sweden. Taylors Falls was the primary gateway for the earliest Swedish settlers coming on steamboats up the St. Croix River and the many thousands who followed, establishing settlements throughout Chisago County. The first four Swedish families to the Taylors Falls landing on April 23, 1851, were met by another Swede, Eric Nordberg, whose letters enticed them to come by steamboat from Moline, Illinois. The history of this first-party came alive in Vilhelm Moberg’s novels and the motion pictures “The Emigrants” and “The New Land.”

By the late 1800s, the logging industry was approaching its crescendo and dairy farming was in full stride. Steamboats and railroad cars were brimming with immigrants and travelers and the 1856 bridge allowed to them to explore both sides of the river. The townships were building roads that connected citizens to businesses, each other, and the outside world. Homes, churches, farmsteads, hotels, banks, schools, and shops were built in Gothic or Greek revival styles using primarily St. Croix white pine harvested and milled locally. Bread was made from St. Croix valley wheat and milk and cheese was supplied by valley dairy farmers. Residents were making a good living from logging, farming or both which allowed other trades to flourish. As the century drew to a close, the thriving towns of Taylors Falls and St. Croix Falls found yet another way to capitalize on their community’s assets and the tourism industry was born.

Preservation Leads to Recreation

It didn’t take long for residents of St. Croix Falls and Taylors Falls to realize the bounty of natural beauty and scenic wonders right outside their front doors. In an effort to protect these treasures, citizens began to lobby to create a state park in the Dalles area and in 1895 Interstate Park was formed. Spanning both sides of the river and maintained by the Departments of Natural Resources in Wisconsin and Minnesota, it was the first park in the United States to be located in two states.

By the summer of 1897, tourists from all over the country were eager to see the new park. Artists distributed works of the astounding views and enthusiasm was rampant. Coordinated railroad and steamboat excursions to the park were teeming with excited visitors and inns and restaurants were filled to capacity. Although the tourism industry faced competition from loggers for rights to the riverway, visitors would continue to find ways to enjoy the tract of amazing beauty within Interstate Park for years to come.

The official government protection kept the park safe from vandals and detrimental logging practices while providing it with the means for improvements. Throughout the 1930s, workers from the Works Projects Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps built structures in the Glacial Gardens and campground areas of the park. The rustic style buildings were constructed primarily of native basalt rock quarried from the valley and are now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1968, the stretch of the St. Croix between St. Croix Falls and Taylors Falls was designated among the first eight rivers of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. The original designation included the St. Croix from its confluence through St. Croix Falls/Taylors Falls and all of the Namekagon River – 252 miles of waterway with boundaries of roughly a quarter mile inland on either side of the river. The purpose of the act was to maintain high quality, free-flowing water, to preserve scenic resources, and to ensure continued public access and recreational opportunities for future generations. Through cooperation with over a dozen organizations, both public and private, the river and surrounding lands near Taylors Falls and St. Croix Falls have become renowned for their healthy forests and clean water and air qualities.

Today, Interstate Park and the Wild and Scenic St. Croix River remain a mecca for tourists enraptured by its scenic beauty. Canoes, kayaks, fishing boats and old-fashioned steamboats ply the river; hiking, biking, and skiing trails lace the forests and countryside on both banks; geology buffs and visitors from far and wide marvel at the giant potholes and glacial topography; bird watchers revel in the diversity of avian natives and travelers of the protected migratory highway; campgrounds dot the shores, islands, and nearby parks, while cabins, inns and restaurants welcome a variety of outdoor enthusiasts and those seeking the health benefits of the reinvigorating air.

What You Can See Today

Glacial potholes at Interstate Park: Glacial meltwater sediment swirled with such great velocity as to drill holes in the hard basalt lining the St. Croix River. More than 100 potholes pock the landscape on both sides of the river, the deepest measuring in near 70 feet deep. It is the largest concentration of these formations in the United States and only one other site in the world in Switzerland rivals it.

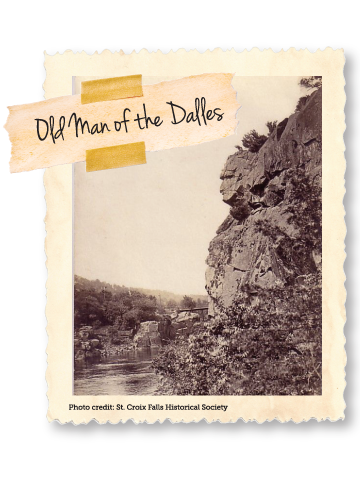

The Old Man of the Dalles: The Dalles of the St. Croix, where river rapids flow through a deep gorge cut into the ancient bedrock, is home to the Old Man of the Dalles, a natural rock formation standing sentinel over the river.

Eskers: These spine-like, winding ridges formed by retreating glaciers can be trod upon at Interstate Park trails.

Ice Age Interpretive Center: Learn more about glaciation in Wisconsin and Minnesota at the Ice Age Interpretive Center at Interstate Park. The center shows a short film, houses various displays, and provides information on how to best view the natural phenomena of the area.

Site of the Battle of the Dalles: Around 1770, the Dakota and Fox tribes engaged a massive force of Ojibwe at the Dalles of the St. Croix. The Ojibwe were near defeat when timely reinforcements arrived to turn the tide of battle. Both sides suffered heavy losses, but the Ojibwe emerged victorious, temporarily seizing control of the Upper St. Croix valley and setting an informal boundary near the mouth of the Snake River. The rocky shoreline and “boiling” rapids of the dalles at St. Croix Falls look much the same as they did at the time of this battle.

1825 Treaty Boundary: An 1825 treaty established a boundary between the Dakota to the south and the Ojibwe to the north at Cedar Bend where the St. Croix River elbows eastward, near the Washington-Chisago County boundary, just north of Falls Creek Scientific and Natural Area off MN-highway 95.

“St. Croix River” on maps and signs: The St. Croix River has had many monikers. Riviere Trombeaux (French for River of the Grave) was coined by Father Louis Hennepin in 1683, possibly referring to a Native American gravesite. Jean-Baptiste-Louis Franquelin’s 1688 map which sited Fort St. Croix at the mouth of the river and a grave marked with a cross belonging to a French voyageur, possibly a fur trader named Sainte-Croix, likely contributed to the more widespread use of Riviere de Sainte-Croix (French for Holy Cross). Ojibwe language names include Gichi-ziibi (Big River), Manoominikeshiinh-ziibi (Ricing-Rail River), Okijii-ziibi (Pipestem River), Jiibayaatig-ziibi (Grave-marker River – to commemorate the many battles between the warring Ojibwe and Dakota fought on the shores of the river). An 1830 map designates the St. Croix as the Chippewa River, but in 1843, Joseph Nicollet’s writings reinforced the name St. Croix, providing a lasting testimony of the French influence in the region.

Trading posts: Although fur trading posts were once scattered along the St. Croix River and its tributaries, few remain today. Federal Indian Agents, tasked with keeping the peace between the feuding Dakota and Ojibwe, removed many of the posts near the tribal boundaries in an effort to keep the groups separated. An American trading post about four miles upstream of Taylors Falls was burned by Agent Henry Rowe Schoolcraft in 1832 because the Dakota and Ojibwe were “improperly brought into contact.” A 1753 French fur post was once located at the mouth of the Sunrise River on the grounds of what is now Wild River State Park. The Snake River Fur Post near Pine City, MN is a reconstruction of the British North West Company’s 1804 trading post. Now owned and operated by the Minnesota Historical Society, visitors can view exhibits, learn about the fur trade, and explore the grounds of the valley’s earliest global trade.

Angle Rock: The St. Croix River narrows considerably at the Dalles and the water quickens its pace. From the Minnesota shoreline, a large promontory juts into the channel, sharply changing the angle of the river. As logs careened between the sheer, confining trap rock walls of the Dalles, they were often unable to make the 90-degree turn at Angle Rock, causing backups for miles, halting all lumber production in the valley.

Nevers Dam: As log jams at Angle Rock increasingly vexed lumbermen, Frederick Weyerhaeuser undertook to eliminate them by constructing Nevers Dam. In 1889 he spent $250,000 to build the largest wood-piling structure in the world 11 miles upstream from the jam site. The 614-feet-wide dam featured an enormous bear-trap gate to control water flow, a holding pen with 15 sluice gates, and electric lights to allow for round-the-clock sluicing. Nevers Dam was removed in 1955, but the ice breaker islands and earth works are still visible at Nevers Dam Landing and Wild River State Park.

Original St. Croix Boomsite: Originally owned and operated by men of the Osceola, Taylors Falls, and Marine on St. Croix area, the boomsite was located near Osceola Landing before eventually moving to Stillwater to more effectively service the large flow of timber from tributaries further downstream.

The First Saw Mill in the Valley: In the spring of 1839 Lewis Judd and David Hone formed the Marine Lumber Company in Marine on St. Croix and built a fully operational mill by fall. The remains of this mill rest beside the mill stream, marked with interpretive signs, in the heart of historic Marine.

The St. Croix Falls Lumber Company: Immediately following the treaty of 1837, the St. Croix Lumber Company began construction on a mill at the falls, but the inexperienced crew faced so many building challenges on the site that it was not completed until 1842. By that time, it was realized that the Dalles was not an ideal location for a mill and lumbermen opted to float their logs further downstream. Although the company did not find much success with their mill, they are credited with sending the first log raft downriver to St. Louis. High waters allowed their entire stock of logs to escape the company’s boom and float away with the current. The men had to act fast to wrangle two million feet of runaway logs which were then organized into rafts and floated down the Mississippi to St. Louis for sale. Thereafter, log rafting down the Mississippi became common practice for St. Croix lumbermen. The vestiges of this enterprise are long gone, but their presence was instrumental in forming the early history of St. Croix Falls.

Old barns and farms: The rolling farm fields of the valley serve as a testament to its dairy farming roots. Many of these homesteads are still privately owned and in use by the families who initially established them and contain barns and farm houses over a century old.

SOO Line Railroad: Railway excursions in the St. Croix valley can be experienced much as they were over 100 years ago. Vintage trains depart from the fully restored 1916 depot in Osceola and travel south along the bluffs of the St. Croix to William O’ Brien State Park in Marine on St. Croix or east through the picturesque countryside to Dresser, WI.

Taylors Falls Scenic Boat Tours: History cruises on the St. Croix River let visitors see through the eyes of fur traders, Native Americans, lumbermen, and immigrants as they learn about these river trades, local geology, river commerce and more, all while taking in the impressive views of the Dalles and beyond.

The Immigrant Trail: Minnesota State Highway 95 runs parallel to the St. Croix River and has been dubbed the Immigrant Trail. Many Europeans followed this path to the valley and destinations along the route document the rich history of early settlers in the region. Mile posts 39.5-55.1 encompass the area between Marine on St. Croix and Taylors Falls with stops such as William O’Brien State Park, the Swedish Gammelgarden Museum in Scandia, the Falls Creek and Franconia Bluffs Scientific and Natural Areas, Cascade Falls in Osceola, the historic districts of Franconia and Osceola, Interstate Park in Taylors Falls, and much more.

Town House School: Built in 1852, the Town House School building once operated as a combination town house and school serving Taylors Falls. It is Minnesota’s oldest remining public school building and is still in use today for tours and school programs.

W.H.C. Folsom House: Originally from Maine, Folsom came to the St. Croix valley in search of work. He became a prominent community leader in Taylors Falls and a Minnesota state representative and state senator for six terms. His early work brought him up through many of the valley’s most important trades, including farm labor, logger, camp cook, and mill builder before he became a business man with investments in a lumber mill, hotel, and the first bridge across the St. Croix River. The Folsom house was built in 1855 and houses many of the family’s original furniture and belongings.

Angel’s Hill District: This collection of early homes in Taylors Falls are constructed in Greek revival style with a New England variation. The buildings are almost all built with a solid white pine frame covered with white clapboard and trimmed with green exterior blinds. The Folsom House is part of the historic Angel’s Hill District.

Taylors Falls Public Library: Originally built as a tailor’s shop in 1854, the Taylors Falls Public Library was remodeled and converted in 1887. Constructed from local resources, its sandstone foundation and white pine frame with Gothic revival and New England style embellishments reflect the popular architectural style of the region in this period. The library continues to operate in this building with a collection of over 10,000 works.

Taylors Falls Saloon & Jailhouse: In 1869, a one-story stone structure with an indoor cave was built as a saloon. Later a two-story stable and livery, built in 1851, was purchased from the Chisago House Hotel and placed atop the saloon as living quarters. In 1884, a jailhouse was constructed next door of stacked 2×4 boards with four jail cells inside. The original iron door and bars on the windows still adorn the structure. Each building housed various businesses throughout the years, but now they function together as a bed and breakfast.

Taylors Falls Depot: A lasting vestige of the railroad era, the Taylors Falls Memorial Community Center once served as a depot for the Northern Pacific Railway. The stylish and functional building with Craftsman and Shingle style construction was built in 1902 and brought a community together through tourism and commerce until 1948. Today, it continues its tradition as a meeting place for the town of Taylors Falls.

Cushing Land Agency: Caleb Cushing established an agency in 1854 to sell his preempted property in the St. Croix Falls area to the public. In 1880, a fire destroyed his original office and a new office was built in 1882, run by Joseph Stannard Baker. The Queen Anne style building changed its name in 1911 to the Baker Land and Title Company and is in use today as the St. Croix Falls Historical Society Museum.

Lamar Community Center: Built as a one-room school house in 1905, the Craftsman style structure with Italianate tower was a principal landmark in the community of Lamar. In 1910 a second southern room was added to the school and further renovations were undertaken in 1926. It is the only remaining structure of the once thriving town and it now functions as a community center serving to unify people as it always has.

St. Croix Falls Civic Auditorium: At the end of the logging era, the burgeoning community of St. Croix Falls was hungry for culture. In 1917, the St. Croix Falls Civic Auditorium finally answered the call. The civic center boasted a kitchen and gymnasium that served many community functions. Throughout history, the center hosted a variety of enterprises including many years as the home of the Festival Theater.

Thompson House: Thomas Henry Thompson was a St. Croix Falls community leader whose 1886 general store was the primary mercantile outlet in the region. He later acted as vice president of the Bank of St. Croix Falls and was a local promoter for telephones and automobiles. His 1882 Italianate style home stands preserved in St. Croix Falls.

Wovcha, Daniel S., and Barbara C. Delaney, and Gerda E. Nordquist. Minnesota’s St. Croix River Valley and Anoka Sandplain: A Guide to Native Habitats. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995

McMahon, Eileen M., and Theodore J. Karamanski. North Woods River: the St. Croix River in Upper Midwest History. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009.

Folsom, William Henry Carman. Fifty years in the Northwest. With an Introduction and Appendix Containing Reminiscences, Incidents and Notes. St. Paul: Pioneer Press Company, 1888.

Dunn, James Taylor. The St. Croix: Midwest Border River. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1979, reprinted with arrangement by Henry Holt and Company, Inc.

“Baker Land and Title Company Records, 1879-1958.” University of Wisconsin Digital Collections, http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi/f/findaid/findaid-idx?page=home;c=wiarchives;cc=wiarchives. Accessed January 2019.

“Folsom House.” Minnesota Historical Society, www.mnhs.org/folsomhouse/learn. Accessed January 2019.

“Snake River Fur Post.” Minnesota Historical Society, www.mnhs.org/furpost. Accessed November 2018.

“Immigrant Trail District (mile post 39.5 – 55.1).” St. Croix Scenic Byway, stcroixscenicbyway.org/PDF/109%20Immigrant%20Trail%20District.pdf. Accessed December 2018.

“Immigrant Trail.” St. Croix Scenic Byway, stcroixscenicbyway.org/immigrant-trail/. Accessed December 2018.

“Geology and Glacial History.” St. Croix Scenic Byway, http://stcroixscenicbyway.org/PDF/101%20Geology%20and%20Glacial%20History.pdf. Accessed October 2018.

“Dakota and Ojibwe History.” St. Croix Scenic Byway, http://stcroixscenicbyway.org/PDF/110%20Dakota%20and%20Ojibwe%20History.pdf. Accessed October 2018.

“Logging.” U.S National Park Service: St. Croix National Scenic Riverway, https://www.nps.gov/sacn/learn/historyculture/logging.htm. Accessed October 2018.

“Stories.” U.S National Park Service: St. Croix National Scenic Riverway, https://www.nps.gov/sacn/learn/historyculture/stories.htm. Accessed October 2018.

“Places.” U.S National Park Service: St. Croix National Scenic Riverway, https://www.nps.gov/sacn/learn/historyculture/places.htm. Accessed October 2018.

“Research: Ruins of a Forgotten Highway.” U.S National Park Service: St. Croix National Scenic Riverway, https://www.nps.gov/sacn/learn/historyculture/upload/SCR-Issue3.pdf. Accessed October 2018.

“Archeological Sites.” U.S National Park Service: St. Croix National Scenic Riverway, https://www.nps.gov/sacn/learn/historyculture/archeological-sites.htm. Accessed October 2018.

“Fur Trade.” U.S National Park Service: St. Croix National Scenic Riverway, https://www.nps.gov/sacn/learn/historyculture/fur-trade.htm. Accessed October 2018.

“St. Croix: A Northwoods Journey.” U.S National Park Service: St. Croix National Scenic Riverway, https://www.nps.gov/sacn/learn/photosmultimedia/multimedia.htm. Accessed November 2018.

“Nevers Dam…The Lumberman’s Dam.” Minnesota Department of National Resources, http://files.dnr.state.mn.us/destinations/state_parks/wild_river/nevers_dam.pdf. Accessed January 2019.

“Taylors Falls Walking Tour: Part 1.” Presented by the City of Taylors Falls and the Heritage Preservation Commission, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tHZjeYAZRV4. Accessed December 2018.

“Taylors Falls Walking Tour: Part 2.” Presented by the City of Taylors Falls and the Heritage Preservation Commission, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=piZrNsO1POQ. Accessed December 2018.

“Town House School.” The Historical Marker Database, https://www.hmdb.org/Marker.asp?Marker=78666. Accessed January 2019.

The Old Jail, http://www.oldjail.com/index.html. Accessed January 2019.

This article was written by Karen Lawrence and produced by Linda Shober Marketing + Design, with input from Barb Young.